|

| The Future Cone: A core concept in design theory on the impact of design to drive change [Source] |

In August 2014, I began a PhD in Design and completed it in May of 2020 at Carnegie Mellon University. I did the program full time and worked full time throughout. I am also a father. Both of my children were born during my time in the program. From 2016-2018, I formally left the program for two years while working for the White House but I continued to work on the dissertation at that time. No doubt, I was very tired and stretched too thin.

I pursued this program with a goal to expand my personal practice into new directions and to reinforce my longstanding history of connecting technology design to economic development. I expected it would lead to a combination of teaching and entrepreneurship. I encountered deep departmental resistance to my work for reasons I never quite understood. Consequently, I very much had to complete my thesis under great stress and with limited channels of constructive feedback. Yet I achieved all of my goals. Over the years I built companies, products, and unique expertise on AI product design. I am glad I did the PhD Design. It was not a waste but it was not what I expected.

Bottom line up front, should you do the PhD design?

At the end of the day it provides a credential, so will you benefit from this credential? I benefit because I immersed myself into communities and research efforts beyond my department and across the university. I worked on a corporate research contract with the CMU Robotics Institute, which is the world leader in its field. I collaborated with persons at MIT where I also served on an investment board. The name recognition, access to resources, the growing community of friends and colleagues, and exposure to writing on design from over the last 100 years had powerful outcomes. Overall, I accomplished my goals.

At the same time, you don't need need a PhD to do much of that. The PhD provided opportunities but those paths were not the lone options available. The culture of many PhD programs is total nonsense. Most academic faculty can't help you do anything but encourage you to be just like them. As reported by Bloomberg, there is only market demand for technical PhDs. So I benefit because I persevered since my goals were to build a technical community, technical expertise, and to build companies. My goals aligned with the market and to create more career options. The PhD credential itself has minimal value unless I seek a teaching position in the future. So if you are interested in the PhD Design, you need to decide what you want first, assess how your goal aligns to the rest of the world, and then decide how to use the PhD experience to make that happen.

If you do not craft clear goals, or if those goals have no value to others, the PhD design will have nominal benefit - or worse, it could be a problem. It is a young degree and few people in the world have one. Individuals around the world hold deep subjective ideas about what Design is as a field. Many people think I decorate houses or design cars. Many engineers think that design is simply a matter of making things pretty or is a tool for marketing. Consequently, you need a very clear plan for using the PhD and proving your value.

Why I did the PhD Design

Prior to the PhD, I had worked in or studied several fields of design including communications, architecture and urban planning. I specialized in working in conflict cities and with displaced, refugee populations. Around that time I also maintained a blog called Humanitarian Space reflecting the previous 8 years of personal practice and published an article on choosing graduate programs. I primarily identified as an urban planner, but with a growing interest in new technologies, sought a PhD program to not just review traditional urban planning subjects. I imagined new planning problems were ahead as robotics and machine learning became integrated in society. The PhD Design seemed like a new way to think about these kinds of problems. There were only a few schools in the world where I could really do this kind of research. I chose the PhD Design program at Carnegie Mellon University because it had a "practice based" curriculum and CMU is the global leader in AI and robotics, and the low cost of living in Pittsburgh. In comparison other top universities in the US and Europe are in more expensive cities.

What is the result of the PhD Design?

For Others - Among my peers from within my program and graduates of other PhD design programs, most are faculty at prestigious universities. They are paid a modest salary as assistant professors at globally top ranking schools, at around $65,000 USD per year. Most faculty I know make between $65,000 and $85,000 USD annually at the world's greatest universities. They are required to teach 3-5 classes per year and demonstrate evidence of other scholarly work or creative practice. Most are not required to bring in additional research funding. Those who do bring additional funds typically earn more money. A couple others are Design Researchers at a big tech companies on the West Coast. They all care a lot about a handful of academic conferences called Cumulus. They publish in niche academic journals like Design Methods and She Ji.

My Personal Experience - It is normal for goals to change over a PhD program in the US. Mine did not, but they became more specific. I had two children and thus became more concerned with the business of my practice. I also became more specifically interested in particular forms of machine learning as an emerging technology. From my two years at the White House, I became focused on combating disinformation as a technology entrepreneur.

Consequently, the PhD Design was a vehicle for executive education. I entered the program as a technical expert and graduated as a business executive. I created a niche specialization in applied AI research. This enables higher earnings while also observing direct consequences of my research in the world. This is a creative practice to solve real problems. The degree was not essential, but it provided a platform to consolidate resources, build expertise, and assert credibility.

Should you do the PhD Design?

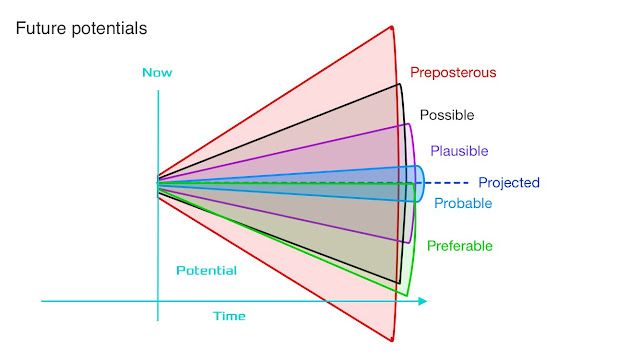

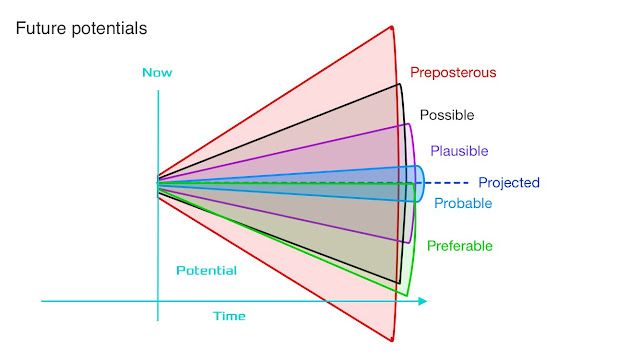

Design is not a study of "what was" but is the study of invention, to invent something new. Designers are forward thinkers, and consequently, the study of design should be grounded in theories on creating something new. To some extent the PhD Design does this. Readings by Herbert Simon, Christopher Alexander, Christopher Jones, Horst Rittle or Lucy Suchman do well to orient a designers' thinking on the relationship between making things and human experiences. With research, one can become a better designer for social problems, engineering problems, or otherwise. The PhD in Design could be a compelling path to creative invention.

How to approach a PhD Design program and succeed on the other side

1. Ignore the previous work by the graduate department - what is their plan for future work?

You can review all the work that came out of the department, but as a PhD Design candidate, you will be there 4+ years into the future and the past work doesn't matter as much. Also don't stay 10 years. Just get the damn thing out the door and move on with your life.

2. You need to get friendly with a possible advisor to get accepted but select a program by the culture.

It is common practice to email possible advisors and build a relationship before applying. Do not be afraid, it is part of their job. But you need a catchy email and a reason. That person will advocate for your admission. Feel free to engage multiple persons. But do not expect you will have a great relationship with your preferred advisor. I came to CMU because two people on faculty were rockstars in Design and Human Computer Interaction. Then they both left. These kinds of problems are common. I continued to work with those persons, but they could not be my advisors as they were not in my department. I left the program for a couple years and when I came back it was better. I found two faculty members who avoided the politics and wanted to help me graduate. They knew what constituted a good thesis and provided the necessary support to get it done and graduate.

3. Do great work and NEVER stop fighting for what you want.

If you come to the program with specific goals, do not give up, no matter how much other people do not agree or support you. I was told that my goals were the wrong goals. I was told that my reading selections were the wrong selection. I was told that my presentations were too aggressive. I was told that a focus on business is antithetical to the values of academia. This is total idiocy. These were subjective complaints. As faculty in Design, they have a steady paycheck do not have a real risk if their practice/research endeavors fail to generate any meaningful outcomes in the world. Unless they have done the specific thing you want to do and they are speaking to that topic - their input should be ignored. You own all the risk if your PhD doesn't work out and they have none.

4. Read number 3, again.

Seriously, no one cares about your goals as much you do. If you use the PhD Design for what it should and could be - prioritizing the creation of things that are new - then you will be alone. The more your ideas and work are truly innovative, the more people will criticize what you do and the less they will have to contribute. True innovation is a lonely road. So fight like your future depends on it, because it does. Then celebrate when you achieve the extraordinary. All the naysayers will still be stuck in the same old jobs doing the same old things. You will, however, go on to have great adventures and opportunities ahead.